Legendary swimmer and 1936 Olympic gold medalist Adolph Kiefer has passed away at the age of 98. Prior to his death, he was the oldest living American Olympic champion.

Kiefer passed at his Illinois home at 6:00 in the morning on Friday, May 5. He was a month shy of his 99th birthday.

The International Swimming Hall of Fame published a lengthy obituary today, recounting Kiefer’s legacy both in the pool and out. Kiefer suffered from neuropathy that kept him confined to a wheelchair late in his life, but he continued swimming, as he could still stand up in the water. The ISHOF notes that Kiefer had been hospitalized with pneumonia in recent months.

USA Swimming also released a statement on Kiefer’s passing, including this quote from interim Executive Director Mike Unger: “Adolph Kiefer embodied swimming and lived it every day of his life. He was a pioneer for our sport in the truest sense of the word Adolph was so passionate about swimming and exuded it to everyone. When you met him, he made you feel so special and he was amazing to be around.”

Kiefer won the 100 meter backstroke at the 1936 Berlin Olympics, setting an Olympic record that would stand for 20 years. He was also the first man to break one minute in the 100 yard backstroke, doing so as a high schooler in Illinois. He would go on to swim for the University of Texas.

Kiefer served in the U.S. Navy during the tail end of World War II and forged a career in business after his military service. Kiefer was inducted into the International Swimming Hall of Fame in 1965 as a member of the first Hall of Fame class ever inducted.

You can find the full ISHOF obituary for Kiefer below:

Wadsworth, Illinois, Friday May 5. – Adolph Gustav Kiefer died at 6:00 o’clock this morning at his home in Wadsworth, Illinois. The great swimmer, lifesaver, innovator and entrepreneur whose passion for swimming was an inspiration to all who met him, was 98 years and 11 months old. At the time of his death he was the world’s oldest living Olympic gold medalist.

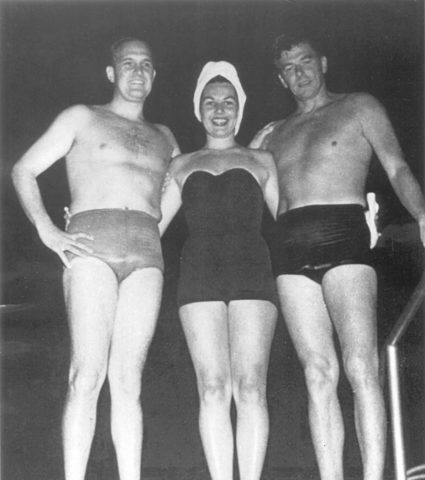

Adolph Kiefer with Johnny Weismuller. Courtesy of ISHOF.

In recent years, the greatest all-round swimmer of his generation was afflicted by neuropathy (nerve damage that causes weakness, numbness, and pain) in his legs and hands that kept him in a wheelchair, except during his daily swims, where he was able to walk again in chest deep water. The water, he said, is what kept him alive, even after the loss of his beloved wife, mother of his four children, business partner and best friend, Joyce, to cancer in May of 2015. They had been married for 73 years. With the support of his incredible family, he emerged from grief and resumed his weekly bridge games and social life. In spite of his incredible life, he never dwelled on the past, but was always thinking about new ways to end drowning and promote swimming. In recent months, he had been hospitalized with pneumonia and longed to be reunited with his beloved wife. He was an incredible man and his passing is truly the end of an era – as the last of the immortals from the first golden age of American swimming that included Duke Kahanamoku, Johnny Weissmuller, Gertrude Ederle, Eleanor Holm, Buster Crabbe and Esther Williams.

As a child he hated getting water up his nose; so, he swam on his back. His father, a German born candy-maker died when he was only 12, but had encouraged his son to be the “best swimmer in the world”. Working furiously to make this a reality, he swam in any pool he could find. On Sundays, when the Wilson Avenue YMCA was closed, he would hop onto trucks, jump streetcars, anything to get to the only available pool, which was at the Jewish Community Center. He firmly believes that the reason he became a world champion is simple, he loved swimming more than anyone else.

At the 1933 World’s Fair, he worked as a lifeguard in the Baby Ruth pool, which hosted exhibitions by swimming champions. Kiefer pestered one recognizable figure in attendance Tex Robertson, captain of the University of Michigan swim team, until Tex finally agreed to coach him. That Thanksgiving, Adolph, then 16 years old, hitchhiked to Michigan where Robertson coached him. “Who’s that kid in the pool?” asked Michigan’s legendary coach, Matt Mann. Robertson replied, “Kiefer, I’m helping him.” Taking out his watch, Mann said, “Let’s see that kid swim a hundred”. Kiefer swam it. Mann looked at his watch and said — “I don’t believe this … do it again!” Kiefer did. Dumbfounded Mann replied, “You just broke the world record — twice!”

A few months later, while swimming in the Illinois High School Championship meet, Kiefer made it official, becoming the first in history to break one minute mark in the 100 yds backstroke. After the meet, his coach, Stanley Brauninger, of the Lake Shore Athletic Club, predicted that the six foot, 165 pound youth would put most of the world’s backstroke records beyond reach of his competitors by the end of the year. His prediction proved right. As a rookie member of the USA National Team at a meet in Breslau, Germany, on November 10, 1935, Adolph smashed the world record for the 100m backstroke with a time of 1:04.9. The listed world record was 1:08.2. One year later, he broke the world record three more times on his way to winning the gold medal in the 100m backstroke at the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games. It was one of only two events won by an American male swimmers that year.

When Kiefer was ready for college after the Berlin Olympic Games, he chose the University of Texas, where Tex Robertson was the coach.

Leading up to the 1940 Olympic Games, as a college student at the University of Texas, Kiefer compiled one of the most impressive records in sporting history, winning National Championships not only in the backstroke, but in freestyle and individual medley races as well. Some of his records lasted 15 years or more. Kiefer’s aquatic achievements earned him an audition for the movie role of Tarzan, but instead of answering the siren call of Hollywood, he heeded the call of Uncle Sam and signed up for the U.S. Navy.

Because of his background as an athlete, he was commissioned directly as a Chief Petty Officer and assigned to Norfolk, Virginia, for “the Tunney fish program,” nicknamed so for Gene Tunney, a former Navy man and heavyweight boxing Champion of the world. The program was aimed at fast recruitment of athletes to form a cadre of physical training instructors who would whip thousands of Navy recruits into condition as quickly as possible.

Once in Norfolk, Kiefer discovered something odd about the Navy. He found that many of the officers and enlisted men he worked with couldn’t swim. Norfolk was also where the survivors of merchant and naval ships torpedoed off the east coast by the Nazis, were brought and he was bothered by the stories they told. He started researching the matter on his own time at night and read a report on Pearl Harbor that said seventy-seven percent of all lives lost were due to drowning. The idea that most men in the navy couldn’t swim well enough to save their lives bothered him. He couldn’t sleep at night because he knew the navy was not training recruits properly to save themselves in the water.

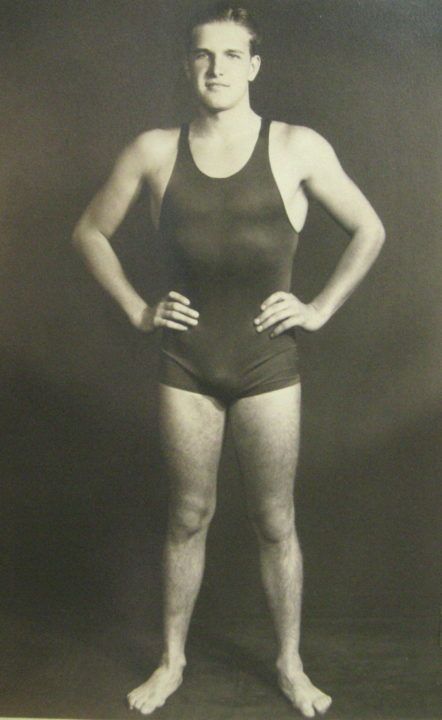

Adolph Kiefer in the Navy. Courtesy ISHOF.

He knew a Captain at the Naval Training Headquarters in Washington, D.C. and on his own, hopped on a train to tell him his concerns. A few days later the captain called, he arranged for Kiefer to meet with an Admiral. The Admiral listened attentively, but showed no emotion and asked no questions. Finally, he said, “Ive heard enough. Why don’t you take lunch and come back in two hours.” Kiefer didn’t know what to think. Because he so critical of the Navy, he even wondered if he might be court martialed for going over the head of his suppers at Norfolk?

When Kiefer returned, the Admiral was all smiles. He said he’d like to know more about what the navy needed to do to protects its men. “When you get back to the base, go see the Commandant and he’ll give you all the assistance you need to write up a program.”

When he got back to Norfolk, he was relieved from teaching, given an office, a yeoman and secretary with a typewriter and devoted himself to reading every life saving manual and report on sinking and shipwrecks he could find. One thing he discovered while he had been instructing sailors to swim was that Fear and Poor Breathing methods were the main reasons why people couldn’t swim. He thought back to his first experience in the water, when he was playing near a canal in Chicago and fell in. He survived by turning over on his back and somehow got to shore. It was not something he had been taught, but whether it was serendipitous or instinctive, that simple movement saved his life – and changed it forever. From that moment on, he felt comfortable and relaxed in the water, he said, because he could breathe naturally and didn’t have his face and eyes in the water and could see. This was the genesis of a new program he called “The “Victory Backstroke.”

Armed with the “Victory Backstroke,” he outlined an intensive learn-to-swim and water survival program that required sailors to receive 21 hours of aquatic survival training. He was then transferred to the new Physical Instructor’s School in Bainbridge, Maryland and oversaw the recruitment and training of over 13,000 naval swimming instructors, including seven “colored squads,” of which there were 70% non-swimmers, yet qualified 100%. These instructors in turn taught over 2 million recruits how to swim and survive a sinking.

One of the many great swimmers Kiefer recruited to the instructors program was Julian “Tex” Robertson, who had mentored him while still in high school and who was his coach at Texas.

Now Kiefer was in charge and once Robertson passed the instructors course, Kiefer sent him to San Diego. After a year, Tex felt guilty about staying in the states and requested an assignment to the front lines. But Naval command had a different mission for him. His persona, training style and techniques had caught the eye of his superiors. He was promoted to Chief Petty Officer and reassigned to train members of an elite special forces unit being formed in Fort Pierce, Florida. Another instructor Kiefer had recruited and who had been selected for Fort Pierce was Tom Haynie, also a swimmer from Michigan. Instead of teaching raw recruits the “Victory Backstroke” they were now preparing experienced swimmers for the first Underwater Demolition Team “Frogmen” – known as UDTs – the forerunners of the Navy Seals.

UDT training began with an “Indoctrination Week,” which compressed an arduous and brutal eight-week physical training program into one week. For twelve to sixteen hours a day, trainees went through physical and mental hell, with each day more difficult than the last. To help ensure safety and maintain morale, the trainers, including Robertson and Haynie, were required to go through this “Hell Week” with the trainees to demonstrate they had the same capabilities and could endure the same hardships as their men. After “Hell Week” Tex and Haynie continued to train the swimmers, but the trainees were also trained in explosives and special warfare tactics and to accompany them on training missions in the most extreme and dangerous conditions imaginable. By the time the trainees graduated as Frogmen, they were some of the toughest commandos in the world, and would play a pivotal role in reconnoitering and clearing obstacles in advance of the invasion of Normandy.

Adolph Kiefer with Ronald Reagan. Courtesy of ISHOF

After establishing his program at Bainbridege, Kiefer turned his attention to the Navy’s lifesaving devices: rings, buoys and lifejackets. When he returned to civilian life, Kiefer established Adolph Kiefer & Associates in Chicago, a highly successful business that he ran until 2014.

Tex Robertson left the Navy after the war and returned to Austin, Texas where he continued to coach and establish an extremely successful summer camp. Since 1946, over 75,000 children have attended Camp Longhorn, including George W. Bush.

After Tom Haynie became a very successful swim coach at Stanford University.

Another Kiefer instructor was Harold Henning, who later became a dentist and successful swim coach at North Central College in Illinois. He also rose to the position of President of FINA, the international governing body for the aquatic sports in the Olympics and was the founding father of the International Swimming Hall of Fame.

Kiefer’s first successful product was the “Kiefer” suit. The silk shortage from WWII caused Kiefer to consider using nylon fabric for suits as the full body competitive suit requirement had just been lifted. Adolph offered a viable option to the wool suits still worn by many beach-goers. The “Kiefer” suits were great for swimmers, improved everyone’s time, no matter how risqué for the era.

His next great product was the wave eating lane line. Kiefer got the idea for the product from Yale’s legendary coach, Bob Kiphuth, who was looking for something that would reduce the waves at Payne Whitney Gymnasium’s pool. Up to this time, lane lines were made of rope with a cork ball spaced every three feet. Kiefer put his mind to work. He noticed the plastic mesh bags that were typically used for packing citrus fruits. He used the mesh idea to create a hard plastic mesh cylinder that became the first commercial wave eating lane line.

Kiefer also was one of the first to distribute and make popular Duraflex Diving Boards for his friend Ray Rude. Duraflex is now the only competitive diving board used world-wide.

Over the years, Adolph Kiefer & Co. has been an official supplier to both the USA Olympic Team and the Olympic Games. He has donated his time and money to efforts helping youngsters learn to swim – even supplying pools in impoverished neighborhoods. Into his early 90s Adolph Kiefer maintained an ambitious schedule of lecturing and promoting the benefits of swimming around the world.

“There will never be another like Adolph Kiefer,” says Bruce Wigo, President of the International Swimming Hall of Fame. “Not only was he a great swimmer and businessman, but he was a great human being, husband and father whose memory will live on as a model and inspiration for future generations of swimmers and non-swimmers alike.”

The family has not made any arrangements for a celebration of Adolph’s life at this time. More details to follow as they become available.

Remarkable man, remarkable career. This obituary should be distilled and become required reading for all young swimmers. What the mind can conceive … RIP

Adolph was not only a stand alone world class Olympic , international and National but more important and American Patriot. He loved the sport of swimming and made it a priority in his life, supported by his wife Joyce and family.. I never met anyone that did not respect and like him for his outgoing friendly personality, honesty and loyalty to his friends. He was a role model for anyone involved in sports.I will forever remember Adolph him and count t him as one of my friends.

Awesome story, I’d never heard of him. I’d give him true hero status for his contributions to the US Navy.

Adolph was funny, gracious, humble and totally committed to teaching the world how to be safe in the water. The US Olympic Alumni Association (USOPA) chose Adolph as the first recipient of the Louis Zamperini Lifetime Achievement Award in 2016. The world and the sport will not soon see anyone like him. RIP, Adolph.

My first race suit. 1971. How many lives did he save, we’ll never know.

His Kiefer PE swim suits are great. They fit extra sizes and you can even sprint in them,

Fascinating story of a great Olympian and humanitarian.

Amazing man. RIP

Adolph was a True to life Hero! I will miss him deeply. 3NT!