Courtesy: Charge Schmerker

The World Championships have come and gone with Caeleb Dressel giving us another jaw-dropping set of performances. He amazed us with his explosive starts, underwaters and his resilience…..all while performing at an extremely high level in as many as three events during a single finals session. Like many of you, I have watched and rewatched his performances in both the 2017 and 2019 World Championships to the point where my wife (a non-swimmer) asks me ‘Are you watching that swim race again? You already know what happens!’.

Why yes dear, yes I am.

Confession: I’ve always enjoyed watching past competitions to see different techniques, great performances and the evolution of strategies. (go watch the 1984 LA Olympics for some cringe-worthy starts in lanes 1 ,6 and 8:

With Dressel’s races what I found myself going back to watch time and again was his ability to finish with what appeared to be acceleration the last 15 meters of the race. It was uncanny and counterintuitive, seemingly defying the basic assumption that all of us hold about racing. Who among us has ever been in the last 15 meters of a sprint 100 free or fly and thought “I have plenty left in the tank, maybe I should kick it up a notch?”. For Dressel, the answer is seemingly “Hold my beer recovery drink!”.

There has been some debate about whether Dressel was accelerating or simply “slowing down less” than the swimmers around him. The ‘slowing down slower’ theory holds true for most swimmers and most races, with the key question becoming; “Who can slow down the least?”. After 85 or more meters of racing the body is becoming deprived of oxygen and the muscles are tightening up. Legs are dying, shoulders aching and Billy Joel is getting all warmed up as the wall seems to getting further away. Yet Dressel drops his head, picks up his stroke rate and goes no-breath for the final 10-15 meters. But is he accelerating?

The oft-quoted saying goes something like ‘The simplest solution is usually the best’, and in this case that simple answer is ‘No, Dressel is not accelerating.’. However, closer examination of the data reveals some interesting trends that might make your future swimming viewing more interesting. Plus there are a few unverified statements such as ‘Michael Phelps’ turn in the 2016 4×100 relay was the greatest underwater ever!’ and ‘Bernard took that 100 out way too fast!’ that we will delve into as well. So, let’s take a closer look.

First, the Methodology

Thanks to high definition TV, uniform lane markings and multiple camera angles this task is much easier than it would have been a decade ago. I watched each race 8-10 times, pen in hand and finger on the keyboard/mouse. As the swimmer approached the red markings on the lane lines at the 15/25/35 marks I did start/stops at the smallest increments I possibly could, recording the time when it appeared the swimmer reached the middle of each marker. In many cases I also verified with a stopwatch. The 25 marker being much longer than the 15-meter markings made that job slightly more difficult, especially when the camera was not parallel to the swimmer but rather at an angle. Overhead cams make this task relatively easy as you can tell precisely when the swimmer reaches the mark. Underwater views were especially problematic. Some older videos were much more difficult to decipher with lower resolutions, clocks that seemingly jumped by more than a tenth, and lane markings that look haphazardly assembled. Cielo’s 50-free record is most noteworthy for the line lines looking like they were put together by blindfolded children using leftover parts from multiple different pools. Seriously, what was going on there?

After I recorded the clock time on the screen as the swimmer crossed the middle of each distance marker I then went back and found the resulting time for each section (ex: crossing 25m at 9.8 seconds and the 35m mark at 15 seconds meant a ~5.2 second 10-meter segment). I then divided the segment distance by the time which yielded a rate in meters per second. Recording the time for each race at least a half dozen times helped me determine the best estimate of the time and rate.

Are there possible errors? Sure, the clock on the screen could be off. Sometimes the camera went behind an official right as the swimmer approached the marker. Sometimes the race video jumped by a few tenths or, with older video, went fuzzy at the wrong time. Sometimes the wake and splashing of other swimmers made it difficult to tell when the marker was reached, especially in the 50 free and fly. Other times (especially in older videos) when the camera view switched from side view to sky view there was a jump in the race progression not noticeable in regular speed but when slowed down the new angle seemed slightly incongruent with the timing from the previous camera angle. Therefore, it is important to remember that this discussion is not meant to determine the exact speed at which the swimmers traveled, but rather to determine if the swimmer was accelerating during various parts of the race. Also, we are dealing with a small sample size which can make conclusions tricky, although you will see that Dressel is pretty consistent in his speed patterns. Regardless, in order to account for these possible discrepancies I am allowing for up to a one-tenth of a second error in the estimation of the timing on each end of the segment when determining acceleration/deceleration, for a total of 2/10 of a second per segment. Sounds like a lot? This gives us a margin of error of approximately 0.05 meters per second in the speed for most segment distance/time combinations. This is not a true “margin of error” that statisticians use to create confidence intervals, but rather just an allowance for variance in the calculated rates. So if I find that a swimmer was traveling at 1.8 meters per second (mps) in one segment and then 1.85 mps in the next, that would not necessarily be sufficient evidence to declare that the swimmer was accelerating, although I could reasonably assume they were not decelerating. One final note, I only examined swims of note: World Records and/or swims at Worlds and Olympics. I decided that in-season swims may not be representative of the swimmers real ability or race strategy due to various possible confounding variables. So in the name of nerdery and post-worlds boredom, let’s dive right and swim through the data(see what I did there?), answering the question in the headline as well as a few other bonus nuggets.

Does Caeleb Dressel Accelerate?

This is kind of like your kid asking you where babies come from. You’d like there to be a nice simple answer to the question that doesn’t result in an awkward conversation, possible confusion, and then more questions or group therapy sessions 20 years down the road. But this is not the case for explaining the genesis of a baby, nor answering our acceleration question.

Here’s an easier question: Do I think that Caeleb Dressel is trying to accelerate? Saying ‘Yes’ might imply that he was intentionally holding something back for those last 15 meters. I do not believe that this is the case. I do suspect that he and Greg Troy are making a conscious effort to develop more endurance for the final 15 meters to maintain Caeleb’s rate from the 65-85 meter section. They know a guy like Kyle Chalmers is going to be charging for that wall like my high school team charged the Pizza Inn buffet after a week-night dual meet in The Woodlands. You do not want to get caught off guard in either situation! All jokes aside, what does the data tell us? Let’s look event by event.

The 100 Freestyle

Dressel’s 2016 swim was the Olympic 100 Free final, and his other 100 Free swims that week followed a very similar pattern. Overall, besides the expected deceleration after the start, Dressel keeps things pretty consistent from the 15-50 meter mark, especially in the 2017/2019 races. The apparent marked deceleration from 35-50 meters is really more to do with the turn as the video for the 2019 race (as a single example) shows he would have touched the wall with his hand at roughly 21.8 – 21.9 seconds for a ~2.0 meters per second rate in that segment. So there is an ever so slight deceleration those last 15 meters. His 2016 race had a pretty significant decrease in speed during the 25-35m segment as the field made up ground on him and improving that segment of the race has been very beneficial for him in recent years.

Coming out of his turn/SDK/breakout in the 2017/2019 races he again keeps his speed relatively consistent between 65-85 meters, especially when accounting for possible measurement variance. Where things get interesting, and where he has really improved over the past 36 months, is his final 15 meters. He is markedly faster in 2017/2019 than in 2016. That ~0.12-0.14 mps translates to roughly half a second over those 15 meters. Accounting for the possible error in measurement discussed earlier (~0.05) there is not definitive deceleration in the last 15 meters compared to the previous 10, although he appears to be significantly slower than he was in the 65-75 meter segment. However, since the clock on the screen is only showing times in tenths of a second, it is conceivable (although not likely) that the differences in the speeds for the 65-75/75-85/85-100 segments could all be negligible in the 2017/2019 races.

For the record, I am going with a conclusion of an ever so slight deceleration after the 75-meter mark compared to the 50-75 rates, but no definitive deceleration in the 85-100 meter segment versus the 75-85m segment. Recent swims show that he is possibly maintaining his speed or only experiencing the slightest amount of deceleration during the final 15 meters of the race..

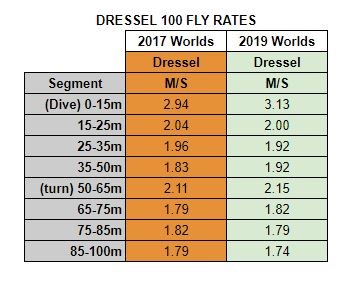

The 100 Butterfly

If you’re wondering where Dressel made his improvements between 2017 and 2019 in the 100 Butterfly, the answer is clearly in his start and in the 35-50 meter segment. His 2017 race showed no definitive deceleration after the 65-meter mark while his world record swim shows that he was significantly slower in the 85-100 meter segment than in the 65-75 segment. Dressel was clearly more aggressive in his 2019 swim over the front half as he was out 0.48 seconds faster than in 2017 as he chased Phelps’ record. That may have led to a fade in his 2019 race as opposed to his fairly consistent 2017 back-half. In contrast, his opening 50-meters in the 100 Free were nearly identical in 2017 and 2019, he just brought the race home a bit faster in 2019.

Dressel is definitely not accelerating in the 100 Butterfly, but he didn’t decelerate in 2017 and experienced only minimal overall deceleration in 2019 over the final 35 meters which I’m fairly certain he was willing to live with given the result.

The 50 Free (and Fly)

Interestingly, Dressel shows clear deceleration in his 50-meter races during the last 15-25 meters, but his butterfly race in 2019 showed a much more consistent rate of speed overall after the initial 15-meters than his 50 freestyle races. His freestyle shows a fairly dramatic deceleration in the 25-35 meter section and then again (albeit less dramatic) in the 35-50 meter segment. This was the most surprising and definitive result of them all, Dressel clearly decelerates during his 50-meter races, although he does a better job maintaining his speed during the middle portion of the race when swimming butterfly.

So, does Dressel accelerate? I think the answer is clearly and definitively “No”. And that comes as no surprise to anyone who as ever competed. The idea is almost ludicrous to even consider if the swimmer has been giving any kind of effort to try and win the race. What Dressel does better than most of his competitors (besides his other-worldly starts) is maintain his momentum over the final 35 meters of his 100-meter races and experience only a minimal amount of deceleration, if any.

This begs the question, what are Dressel’s competitors doing after staring at his feet following the initial 15 meters? I broke down other notable swims from the past decade-plus and performed the same basic analysis. Let’s take a look.

The 100 Freestyle

There’s lots of data and interesting swims to look at, but for the purpose of discussing the title of the article, let’s limit our discussion only the rates over the final 35 meters and also look at different subgroupings of swimmers.

Dressel v Chalmers 2019

You didn’t need the numbers to know that Chalmers was coming home like a freight train that last 35 meters. If that were a 101-meter freestyle Chalmers probably wins. Also not surprisingly, Chalmers doesn’t decelerate. In fact, it’s the clearest example of a swimmer not decelerating that you will see in this entire discussion. We can’t call it acceleration, but Kyle isn’t tapping the brakes one bit. He’s probably never even heard of Billy Joel.

Dressel vs. Adrian/Metella (2017)

This is one of the races that started this discussion back in 2017. In this race Dressel had a huge lead off the start (shocking) but Metella and Adrian closed the gap over the 35-50 meter segment. Adrian lost a bit more on his turn but then kept pace the remainder of the race while Metella fell apart the last 15 meters, losing about half a second over that segment.

Dressel vs. The 100 Free Best

In comparing Dressel to Cielo’s world record, both swimmers had near identical back halves, Cielo had a better front half due to his ability (with a suit assist no doubt) to maintain more of his initial speed during the 15-35 meter part of the race.

In contrast, like Chalmers, McEvoy and Magnussen’s respective swims featured massive back-halves with absurd rates of speed during the 65-85 meter segments. Magnussen had a more marked deceleration than McEvoy but both swimmers had clear decelerations over the final 15 meters unlike Chalmers (and to a lesser extent, Dressel).

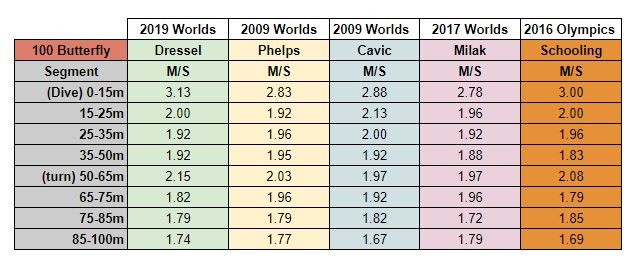

Dressel vs. The 100 Fly Best

Dressel, Phelps and Milak all did a great job of managing their speed the final 25 meters, with Milak (2017) even having a slight acceleration over the final 15. Cavic, to the shock of absolutely no one, had a tough time the final 15-25 meters and Schooling had a similar experience in the 2016 Olympics although his lead was so large it was inconsequential.

Other interesting historical notes.

I went down many a worm-hole during this research, since YouTube likes to keep feeding you “More Videos Like This”. So let’s take a look at one more set of numbers, relays.

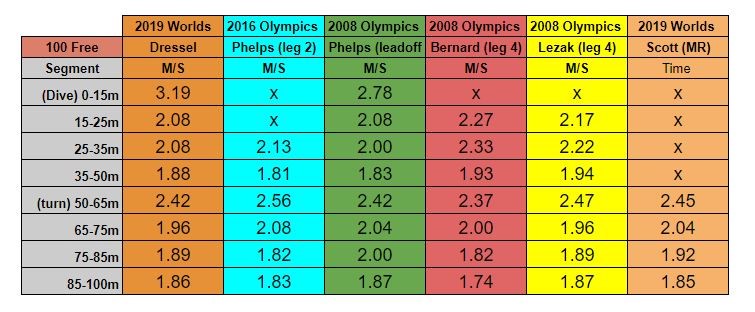

*I ignored splits for the first 25 meters on flying starts for obvious reasons.

Phelps was never known for his early speed in the 100, but he had some killer back halves. His 2008 lead-off on the relay was a classic example as he kept his rate above 2mps for most of the second 50 (Super-Suited, of course). His 2016 swim as the second leg on the relay was also very impressive. That 2.56 on the 50-65 segment being his much discussed turn and his rate stayed constant over the final 25 meters as others were slowing down.

There’s also 2008 Bernard vs. Lezak where you can really see Bernard fall off a cliff the final 25 meters while Lezak made up some ground off the turn and then kept himself together. Bernard’s 1.74mps was the slowest last 15 meters I measured along with Metella (1.73). His 75-85m section was also slow, but not dramatically so. However, his overall deceleration from the initial 75 meters coupled with Lezak’s sustained momentum over the final 25 meters sealed the deal. Yes, he went out waaaaay too fast. Duncan Scott had himself quite a final 50 meters as well, especially considering his lack of a supersuit. Adrenaline is quite the speed and endurance booster.

Speaking of Phelps and those turns. His 50-65 segment in 2016 is rightfully lauded. 2.56 mps is the fastest one I measured and measurably better than all others even when accounting for possible measurement error. AND it was not supersuited. The greatest ever with the greatest turn ever in one of his last swims. GOAT gonna GOAT. Hope you enjoyed the write-up, until next time, just keep swimming.

Its interesting to see how much faster the starts are nowadays- is it because swimmers put more emphasis on this part of the race, or is it the new blocks and rules?

New blocks, new rules, more emphasis, better athletes, no more of that ridiculous swan dive stuff they used to call a “racing start.” I once had a guy show up at my summer league team and start teaching all of my swimmers to basically drag their toes across the top of the water. He was convinced it was the superior start, because in the 1970s that’s how he started.

For those interested, I took the numbers and made some interactive graphs to more easily compare the velocities. http://hdc.cs.arizona.edu/people/kawilliams/swim/dressel-acceleration.html

Interesting to see the 1984 Olympic races. I had dozens of them on YouTube years ago. I attended those Games but my dad was typically thoughtful and taped countless events that he knew I might not be able to see.

I put them on YouTube about a decade ago and everything seemed fine for years until the IOC and NFL started launching copyright complaints. The IOC demanded I remove the Janet Evans races from 1988. It was weird because I had seen Katie Ledecky say she watched those races on YouTube to study Evans’ form. Those were my tapes and now the IOC was insisting they had to be taken down. I complied with everything asked but eventually got… Read more »

Awesome article, loved the insight.

And side note – those 1984 cringe worthy starts…. Even into the 1990s I remember those being taught as the “how to”! I still haven’t managed to entirely break some of those bad habits created when I was young. My masters starts are…..nostalgic =0

I remember being taught the pike dive the guy in lane 6 back in the early 80’s

It’s what we knew.

Half the guys in the video didn’t even get their hands into streamline position.

Most aren’t wearing caps.

I mean 35 years is a long time but still..

These are the type of articles we need. Dressel wasn’t being humble when he said Chalmers is a better freestyler than him

I love ‘GOAT gonna GOAT!’ even in his 9th best event!

I have probably rewatched his 50 fly the most…I would be interested to see the last 5-7m broken down. You could clearly see him increase the stroke rate on the last 2-3 strokes and create an even larger gap on the rest of the field…incredible!

If you could pull that off for 4-5 strokes to the finish that WR would be his!!

I wish but I would need every half meter marked and a slow mo camera

If you could get a still camera view, you could use Logger Pro video analysis or a similar program to get velocities through the whole swim. Probably would work just for the start and finish.

Thanks for the great article. I’d be curious to see a comparison between Chlamers 2019 and Chlamers 2016!

I actually have that.

2016/2019 by section.

2.89/2.88. Negligible

2/2.04. Negligible

2.13/2.12 negligible

1.83/1.85 negligible

2.46/2.42 negligible

2/1.96 negligible

1.96/1.93 negligible

1.81/1.96. WHOA NELLIE!!!

Oh my goodness !