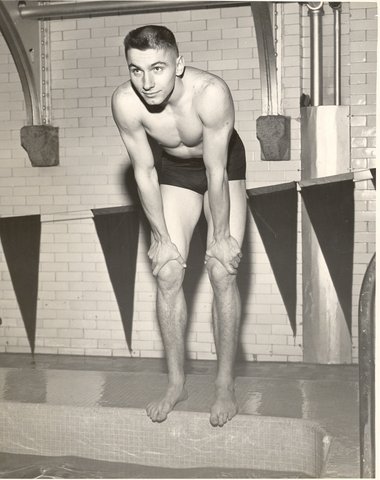

Courtesy: Tom Slear

Don Kutyna’s timing was pretty good.

In fact, it was impeccable.

He came up when the rules allowed for breaststroke to be swum with a frog kick and a butterfly pull. That didn’t work out so well for him. Though he had a powerful frog kick, the butterfly pull sapped his strength. It wasn’t long into a race that he could barely get his arms above the water’s surface. His senior year in high school in 1951, he was fifth in the 100-yard breaststroke at the Illinois high school championships. There’s no record of his time, but the winner did a 1:06.5. The national high school record was 1:01.5. Kutyna was not what anyone, including himself, would call a hot recruit. But a rule change, arguably one of the most significant in the sport’s history, dramatically transformed his swimming fortunes.

The 1950s were a dynamic time for competitive swimming. At the start of the decade, circle swimming and interval training were no more than vague notions. Flip turns were rare. Dolphin kick was talked about but never used. Backstroke included little, if any, body roll. And there were only three strokes: freestyle, backstroke and breaststroke.

All of that would change by 1960, in the process remaking swimming mostly into what it is today with the notable exceptions of track starts and underwater dolphin kick. Most important for Kutyna, butterfly split from breaststroke, creating a fourth stroke and launching him from mediocrity to national prominence.

The breaststroke/butterfly conundrum originated in 1933 when an enterprising swimmer named Henry Myers reasoned, quite correctly as it would turn out, that pulling his arms past his hips and recovering them above the water would lead to a faster breaststroke. He unveiled his creation in a meet at the Brooklyn (N.Y.) Central YMCA during the first heat of the 150-yard individual medley (breaststroke, backstroke, freestyle) and beat Wallace Spence, the reigning national champion. The officials didn’t know what to make of Myers’s technique, but they begrudgingly agreed that the rules gave him a pass. The rulebook said nothing about a pull beyond the hips or an above-water recovery. And since Myers retained a frog kick, he stayed on the safe side of the prohibition against up-and-down leg movement. After his win, the butterfly form of breaststroke spread like a brushfire. At the 1948 Olympics, seven of the eight finalists in the men’s 200 breaststroke used a butterfly pull.

FINA had a choice to make. It could do nothing and let conventional breaststroke disappear, or it could create a fourth stroke. It settled on the latter. In 1953, the rules were modified so that breaststrokers had to pull at or below the surface. Butterfly became a separate stroke; essentially what Myers had created with one major difference. The kick could be vertical as long as the legs moved synchronously. This allowed for the far superior, though more challenging, dolphin kick.

(However, the frog kick didn’t disappear entirely from butterfly. For years some coaches and swimmers designated certain laps in a race for frog kick in order to conserve energy. American Bill Yorzyk put that strategy to question when he decisively won the 200 butterfly at the 1956 Olympics with a continuous dolphin kick. The frog kick was finally eliminated from butterfly by rule in 1970, long after butterfliers stopped using it.)

Meanwhile, Kutyna went off to school and swimming at the University of Iowa. About the time FINA implemented the new butterfly/breaststroke rules, he was a sophomore with an 11-year-old car and a girlfriend named Lucy, whom he described as a “beautiful blond” and would eventually marry. Neither the car nor Lucy did much to enhance his chemical engineering studies. He was after a fresh start. While home in Chicago during a school break, he bumped into Pete Witteried, a junior at the United States Military Academy (often referred to as Army or West Point) who was in the middle of an All-American backstroke season.

Witteried looked good in his dress gray uniform and Kutyna was impressed by what he had to say. Perhaps most important, West Point was a haven from the military draft. The Korean War had been gone on for over two years and it seemed like it would never end. Five months later Kutyna was a plebe (freshman) at West Point. If you had told him he was three years away from winning a national title he would have looked at you as if you had two heads.

American swimming adapted slowly and unevenly to the rule changes. As a college coach wrote in the September, 1953 issue of Swimming World, “…the United States has been acting like a pouting child taking one reluctant step after another.”

It wasn’t until 1957 that the NCAA put breaststroke and butterfly on the same plane as backstroke with 100- and 200-yard events and changed the medley relay to include four strokes instead of just three. High school didn’t have a separate butterfly event until 1958. The Amateur Athletic Union, USA Swimming’s predecessor, moved a bit quicker. By 1956 its short- and long-course championships included 100 and 200 breaststroke and butterfly events. Kutyna, a junior at West Point by then, had adapted well to the new rules. He was able to take full advantage of his powerful frog kick without enduring the exhausting butterfly pull.

And there was one other factor in his favor.

When reworking the rules in 1953, FINA failed to close a truck-size loophole related to breaststroke. There had never been a requirement to come to the surface, a point made vividly clear in the 1956 Olympics when Japan’s Masaru Furukawa won the gold medal in the 200 breaststroke doing one pullout after another. He spent 75 percent of the race underwater. It was not only dangerous for swimmers but unappealing for spectators, something akin to watching paint dry. FINA and the NCAA changed its rules, but not until 1957, briefly leaving open a window for Kutyna to do what he did best: underwater pullouts through as much of each lap of the race as his lungs would allow.

No surprise that the 100 yards and 100 meters breaststroke were Kutyna’s strongest races. The NCAA had yet to offer the 100-yard breaststroke (Kutyna finished fifth and second at the NCAAs in 1955 and 1956 in the 200-yard breaststroke), but the AAU gave him a chance to show his best stuff with its inaugural 100-yard breaststroke in the short-course nationals at Yale in April, 1956. He won with a 1:03.0, which set an American and world record. (FINA maintained world records in short-course yards until mid-1957.)

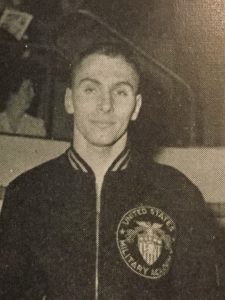

Kutyna in his Army varsity letter jacket after finishing second in the 200 breaststroke at the 1956 long course nationals. Photo: Tom Slear.

However, that race was the beginning of the end to Kutyna’s near-perfect timing. Though he finished second in the 100 three months later at the long-course nationals to Robert Hughes, who broke Kutyna’s yard records six weeks earlier, there was no realistic hope for a spot on America’s 1956 Olympic team. The 400 medley relay wouldn’t become an Olympic event until 1960, and 100 breaststroke not until 1968. He swam the 200 breaststroke at the Olympic Trials in August but finished in the middle of the pack. That was his last race. Though he had another year at West Point, he had used up his athletic eligibility because of the season he swam at Iowa. He spent his senior season assisting with the plebe team.

Kutyna might have come to West Point in part to avoid the draft, but he embraced the military after graduation. He selected the Air Force, which many West Point cadets were able to do before the Air Force Academy graduated its first class in 1959. He stayed on active duty for 35 years and retired in 1992 as a four-star general, the highest rank achievable in America’s military. He’s 86 now and lives in Colorado Springs with Lucy, whom he married the day after he graduated from West Point.

“I had a wonderful career,” he said during an interview in 2016. “USMA and particularly Army swimming allowed me to reach for the stars.”

Funny that there is no direct mention of how Coach Armbruster at Iowa “invented” the butterfly stroke.

Outstanding article. He went to Lane Technical High School in Chicago and was the parade marshal for our Jubilee Anniversary walk from the school to Wrigley Field. Look up the story of the role he played in the Challenger Commission (it involves Astronaut Sally Ride and scientist Richard Feynman).

Don and I were members of Bob Kiphuth’s Olympic training group in the summer of 1956. I still have newspaper clippings and articles

concerning the summer of ’56 at Yale.

pete kennedy

Excellent researched article Tom!

Echoing some of the other comments here, just a well done article about an outstanding individual. Enjoyed learning more about breaststrokes evolution as well.

Anyone else do a double take when they read “11 year old girlfriend named Lucy”?

It says he had “an 11-year-old car and a girlfriend named Lucy”, not an 11 year old girlfriend. Don served as the Commander of NORAD and was a member of the committee that investigated the Challanger disaster.

Don was just named to the Army West Point Hall-of-Fame Class of 2021. Congratulations Don!

You might also want to point out that, despite the pandemic, online classes are still available for the Derek Zoolander Center for Kids Who Can’t Read Good and Who Wanna Learn to Do Other Stuff Good Too.

Absolute beast! 1950s would be a great time to time travel to. something new and crazy was always happening!

I worked a swim meet where some of the officials who swam in the late 60s talked about how circle swimming and interval training were just coming out as they finished college.

I didn’t understand how no one circle swam until I went to an old YMCA pool that was from the 60s early/70s and realized there was no way two adults would fit on both sides of the lane.