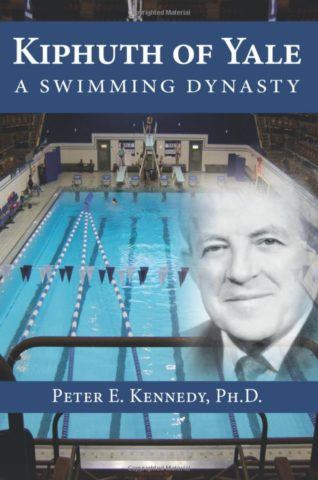

Courtesy of author Peter E. Kennedy, Ph.D., an excerpt from Chapter 8 of “Kiphuth’s Dry Land Program”

By Peter E. Kennedy, Ph.D.

ISBN# 978-0-692-66097-3

Copyright © 2017 by Peter E. Kennedy, Ph.D.

Available on Amazon here

With respect to competitive swimming, Kiphuth, in 1918, was a greenhorn. But he was a wise and observant greenhorn. Kiphuth adopted most of the old methods, but held firmly to his own belief in the physical and well-conditioned body. He ignored the vast majority of experts who insisted that swimmers must have loose and flabby muscles.

There is evidence that others advocated similar dry land exercises for swimmers. Archibald Sinclair and William Henry, in the 1916 fourth edition of their book Swimming, highly recommended gym work. Professor Nelligan, who was at Amherst College at the time, added three-to-five mile walks and slow runs of 800-yards followed by 15 minutes of chest weights or dumbbell work to his swimming program.

Despite those early pioneers, Ed Kennedy, the Columbia University coach from 1910 until 1955, stated that anyone advocating gymnasium work for their swimmer in the early days was considered a lunatic because coaches, with few exceptions, believed that exercise or weight work would destroy the loose, flabby muscles necessary for a competitive swimmer’s success. However, Kiphuth was a physical educator who held fast to the concept that a strong, physically fit body was the key to athletic success. He brought physical training into swimming at a time when others scorned any type of physical activity for their swimmers. It was a novel approach for swimming. Other advocates had come and gone, winning little, if any, support for their cause. They had been theorists, not innovators or achievers. Kiphuth’s dry land program was the result of personal observation, research, and experience.

Despite those early pioneers, Ed Kennedy, the Columbia University coach from 1910 until 1955, stated that anyone advocating gymnasium work for their swimmer in the early days was considered a lunatic because coaches, with few exceptions, believed that exercise or weight work would destroy the loose, flabby muscles necessary for a competitive swimmer’s success. However, Kiphuth was a physical educator who held fast to the concept that a strong, physically fit body was the key to athletic success. He brought physical training into swimming at a time when others scorned any type of physical activity for their swimmers. It was a novel approach for swimming. Other advocates had come and gone, winning little, if any, support for their cause. They had been theorists, not innovators or achievers. Kiphuth’s dry land program was the result of personal observation, research, and experience.

The program was conceived on the principle that developing the proper mechanics of muscle and movement would create a strong and healthy body, beneficial to any athlete, including swimmers. This program, like any other, underwent changes and modifications as Kiphuth’s knowledge expanded. In its most basic form, the routine consisted of 60 minutes of exercise. Included in the 60-minute period were 45 minutes of calisthenics and 15 minutes of work with a 16-pound medicine ball. After that, the swimmers were encouraged to continue on their own with 20 to 30 minutes of pulley-weight exercises.

To partake in Kiphuth’s program was, on the one hand, a physical experience and, on the other, an educational enlightenment. The coach, usually clad in either his white Yale sweat suit or his fireman red long johns, kept a rhythmic cadence by use of a bamboo pole. Mind and body responded automatically to the beat and tempo which was the dictum of either change of cadence or change of exercise. Occasionally, his deep baritone voice permeated the assemblage in order to chastise or encourage a fledgling student. The master’s stick oftentimes missed a required beat in order to be put to better use upon the backside or personage of an incompetent performer. Whether standing in front of or strolling among the gathered guests, he seemed to possess an infallible ability to perceive even the most minute happening within the gymnasium. From the moment of commencement until the moment of termination, one was cognizant of the fact that Kiphuth seemed to be measuring both mental and physical capabilities.

When Richard Mayer, captain of the 1917-18 Yale swimming team, approached Kiphuth in the fall of 1917 requesting assistance, Kiphuth recommended, to Mayer’s astonishment, this radical concept of dry land exercise. Although this represented a revolutionary development, many swimmers accepted Kiphuth’s invitation to “commit suicide.” To the amazement of all, the exercises did not tighten muscles nor cause deficiency in performance. Instead, performance improved. His theory of a program of exercises successfully overthrew the long-entrenched concept that soft muscles made good swimmers.

Unfortunately, one can only speculate as to Matt Mann’s disbelief in January 1918, upon arriving at Yale, that Kiphuth had violated one of the cardinal rules of swimming. His astonishment, as verbally expressed, must have been a classic reductio ad absurdum. Destined to become the Michigan coach, Mann had traveled to New Haven on the weekends during the month of January in 1915, 1916, and 1917, to offer instruction to the Yale squad. During this period, he was dividing his time among at least four programs: the New York Athletic Club, Brooklyn Poly Prep, Lawrenceville Prep, and the Naval Academy.

While Kiphuth insisted on gym work and year-round training, Mann advocated loose muscles, mechanical rabbits, and swimming. According to Karl Michael, Kiphuth’s endorsement of dry land formed a major portion of the professional debate between the two coaches. Fortunately for competitive swimming, this caused two schools of thought to develop. Finally, in the early 1950s, when both concepts had undergone growth and modification, these seemingly distinct but conciliatory approaches raised the sport of swimming to new heights.

To Kiphuth’s credit, he never shrouded any phase of his program in a cloak of secrecy. He publicly advocated his procedures and opened his workshop to the world of swimming. The coach was a true advocate for the advancement of knowledge at all levels of swimming. He never subscribed to the concept that he was the only knowledgeable aquatic luminary, but remained firm in his belief of a well-conditioned body.

Forbes Carlile, the world famous Australian coach, credited Australia’s advance in the late 1940s and up to the 1956 Olympic Games as partially the result of reading, adapting, and modifying the Yale exercises to the needs of their program. In his book Forbes Carlile on Swimming, he mentioned a letter he received from John Marshall, Yale’s Australian import. Marshall attributed his swimming success to Kiphuth’s dry land program, and Carlile cited the letter as further proof of the importance of dry land exercise.

Kiphuth’s dry land program found further disciples at Dartmouth, Princeton, Wesleyan, and various New England prep schools. John Miller of Mercersburg Academy (Pennsylvania) supplemented Kiphuth’s program with cross-country running. Charles McCaffree, who coached at Michigan State from 1941 to 1969, stated that in 1952 his swimmer Bert McLaughlin decided to follow Kiphuth’s program as outlined in his book Swimming. Misunderstanding the text, McLaughlin proceeded to double everything suggested and set a new NCAA record in the quarter mile.

Through the 1930s and into the early war years, many Yale athletic teams, with the consent or insistence of their coaches, took part in Kiphuth’s program of dry land exercises. Yale’s highly respected ice hockey coach Holc York collaborated with Kiphuth in May of 1937 to construct a series of exercises for his team to practice over the summer months to strengthen ankle and thigh muscles.

Bob Giegengack, the Yale track coach, credited Kiphuth as the pioneer who understood the principles of dry land exercise and increased workload. He felt it was due to Kiphuth’s efforts and comprehension of anatomy and physiology that the gap between swimming and track began to narrow.

In general, there is consensus among leading authorities that Kiphuth was the first to institute a bona fide dry land program for swimmers. The concept was not only revolutionary, but also years in advance of its time and is responsible for the innovative practices in existence today. The executive director of the Swimming Hall of Fame, Buck Dawson, credited Kiphuth with bringing “physical training” into swimming at a time when others “scorned” the practice. The French swimming historian Francois Oppenheim credited Kiphuth with being “the first and undisputed leader of dry land exercises.” He pointed out that, “until Kiphuth’s organized approach, the practical application remained, for the most part, an unpopular and untested theory in the evolution of competitive swimming.”

Bizarre and amazing how quickly technical knowledge has developed. That’s like only three generations ago. Thanks for the read.

For those of you who don’t know, Kiphuth is the winningest coach in all of college athletics – not just swimming – with a record of 528 wins and only 12 losses.

Yes but who did he beat? Back in. those days they were slow as dirt.

Don’t dismiss those earlier age swimmers so quickly! In 1965, for example, Yale’s Steve Clark went 45.6 for the 100 yd free – and that was without goggles, no underwaters, old starts, touching every wall on turns, old suits, turbulent water, and old-fashioned lane lines! Who knows what that would equal today – but it would be fast.

My father was at Yale Law from 1930-33. Kiphuth agreed to admit Yale students to his by-then-famous dry land fitness workouts who were not swimmers if they passed a fitness test. I think they also had to attend every work-out. Dad was accepted and never missed a session, at Yale and for the rest of his life. I used to love to watch him work up to the finale of the program, which included 100 push-ups followed by 100 jumping jacks. Dad was fit